“The best way to honour Furtwängler is to play the way Furtwängler did”—Martin Fischer-Dieskau and the Harbin Symphony Orchestra's Furtwängler Tribute Concert

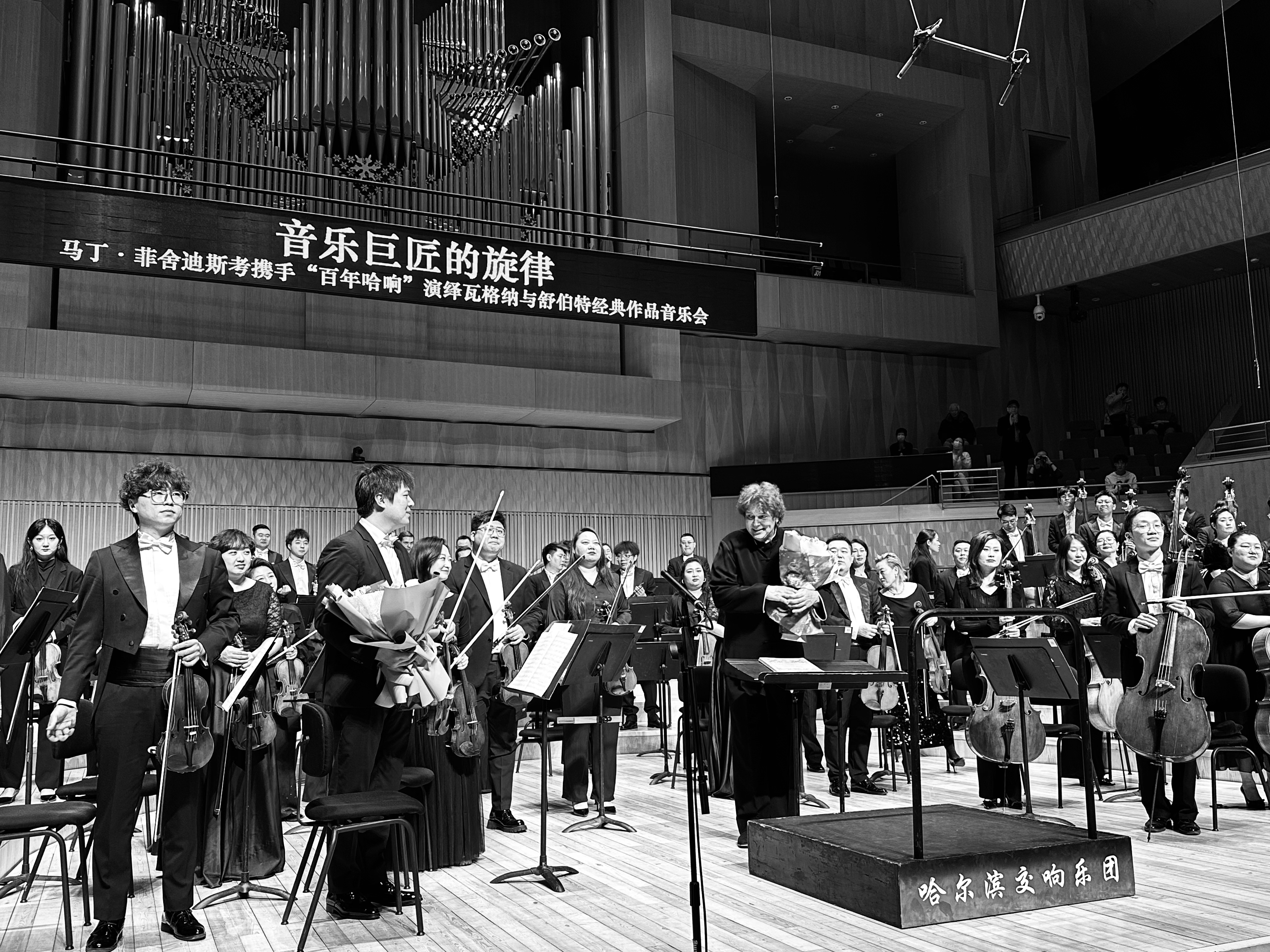

On 29 November 2024, the “Tribute to Wilhelm Furtwängler, the Melody of the Masters—Martin Fischer-Dieskau and the Harbin Symphony Orchestra” concert took place, and classic works of Wagner and Schubert was performed at the Harbin Concert Hall.

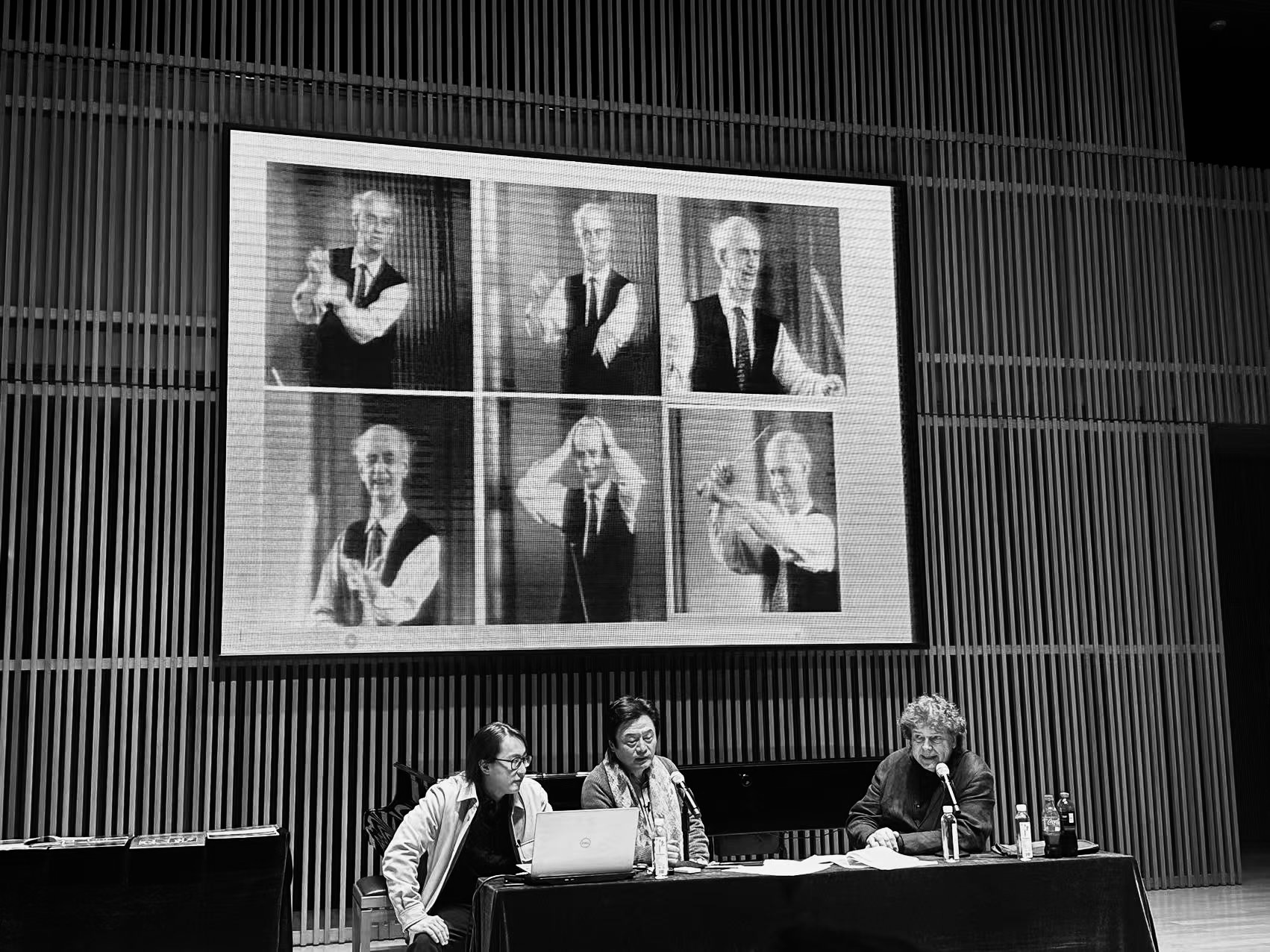

“Our performance is not to imitate Furtwängler, but to play with his point of view, his ideas. Recreating a Furtwängler is impossible and unnecessary. Let the orchestra learn and play Furtwängler’s manner is the best way to remember him”, as Prof. Dr Martin Fischer-Dieskau mentioned in his lecture a week before the concert.

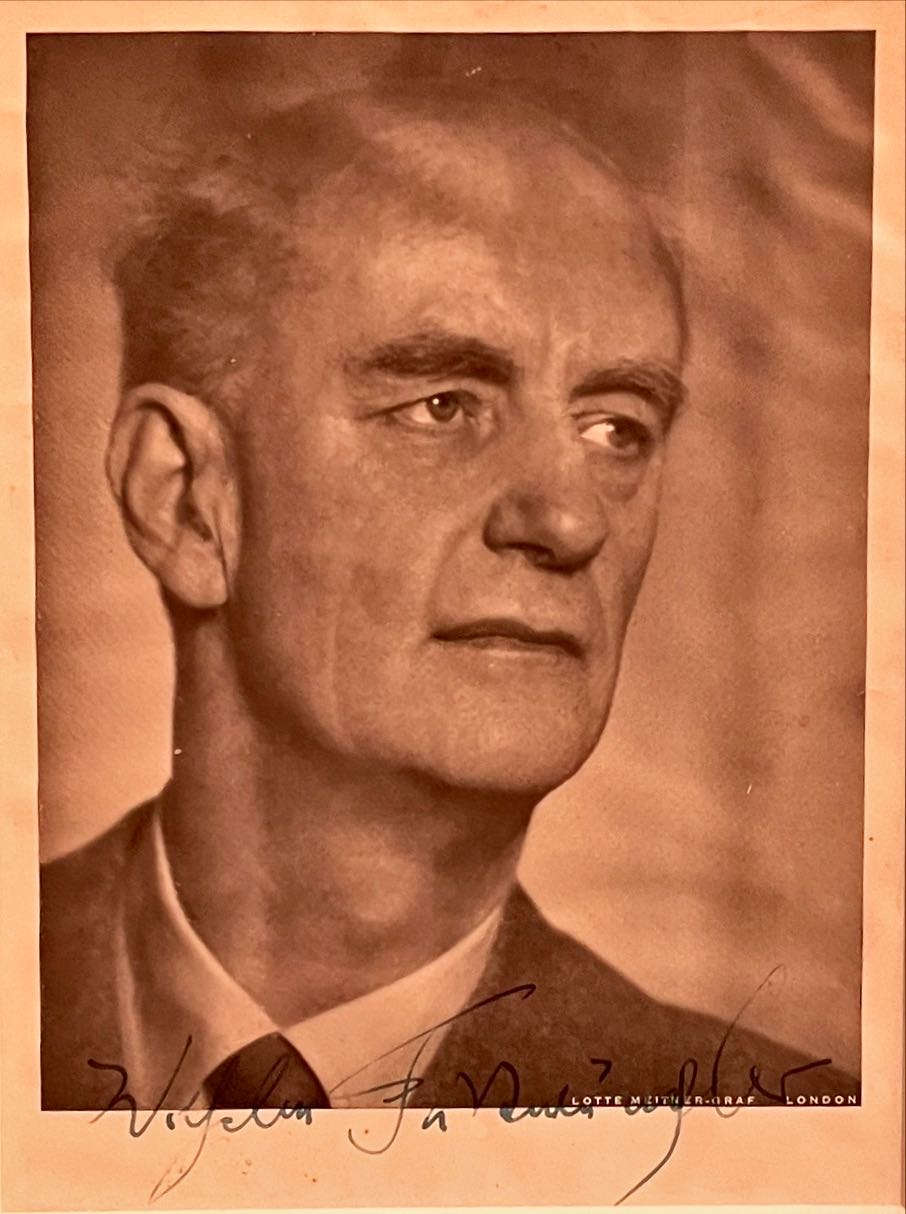

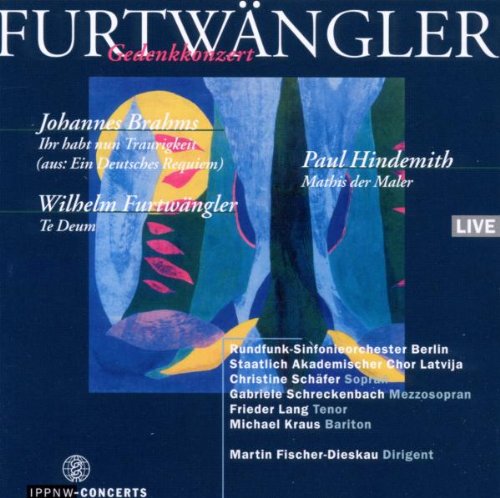

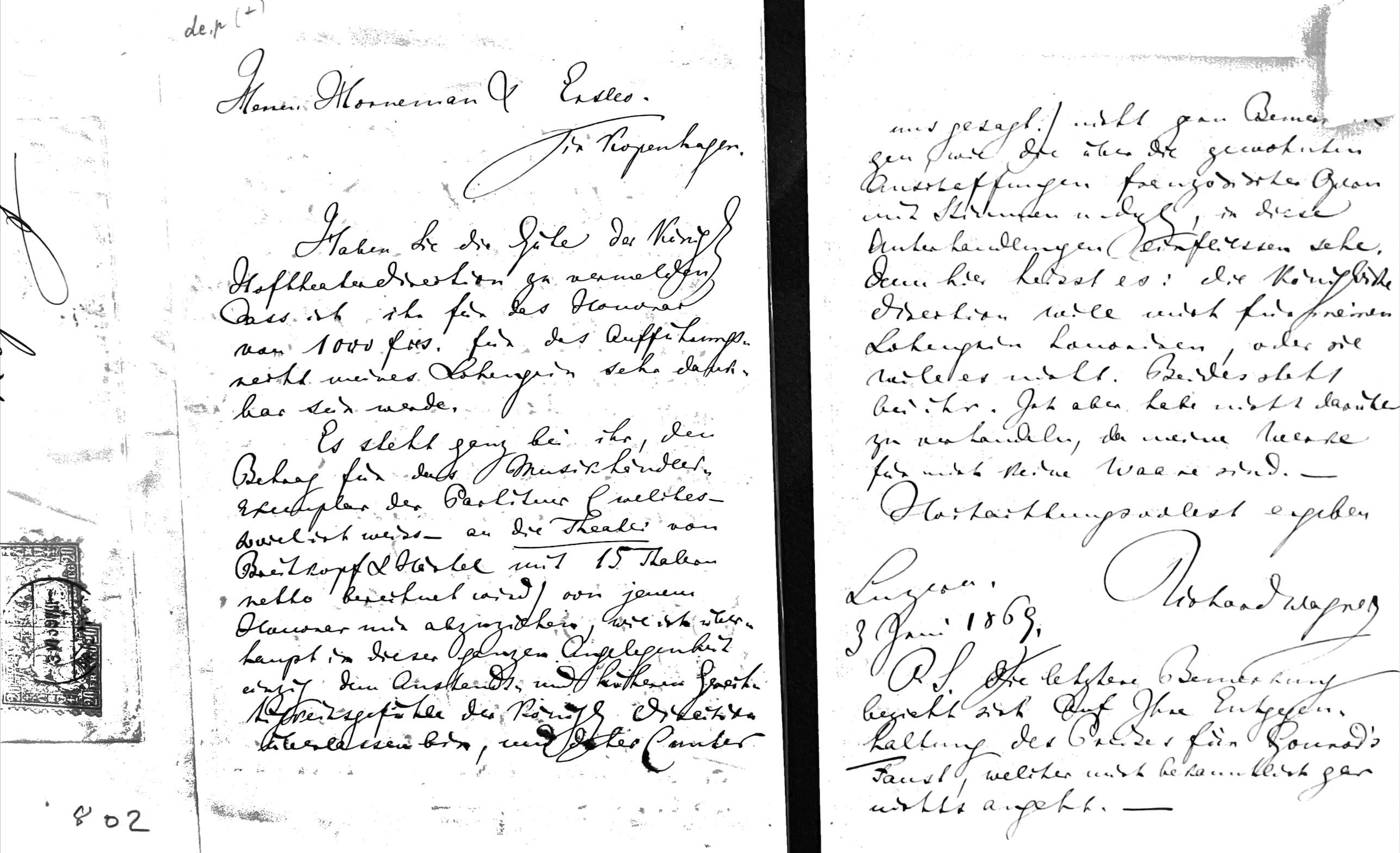

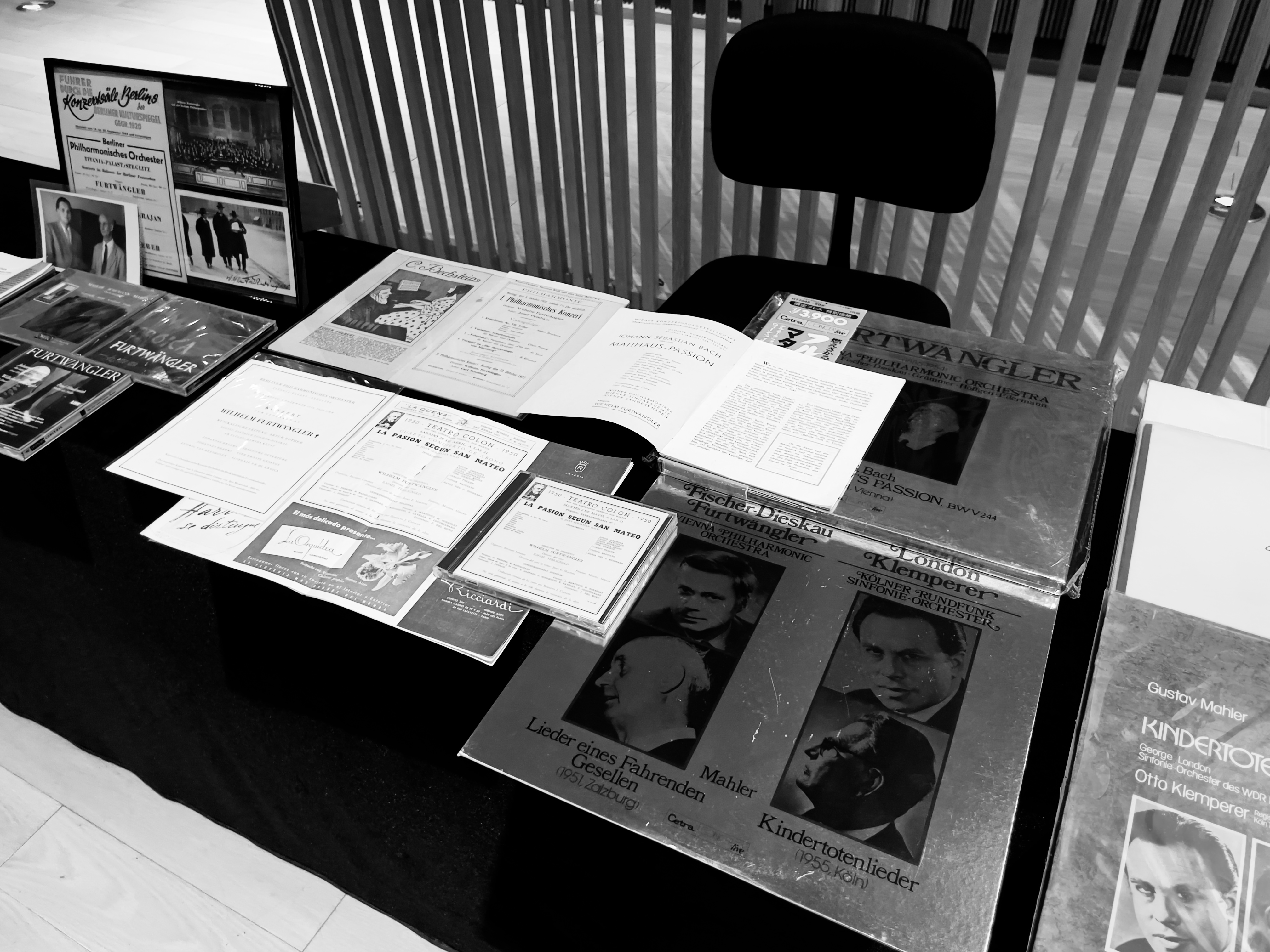

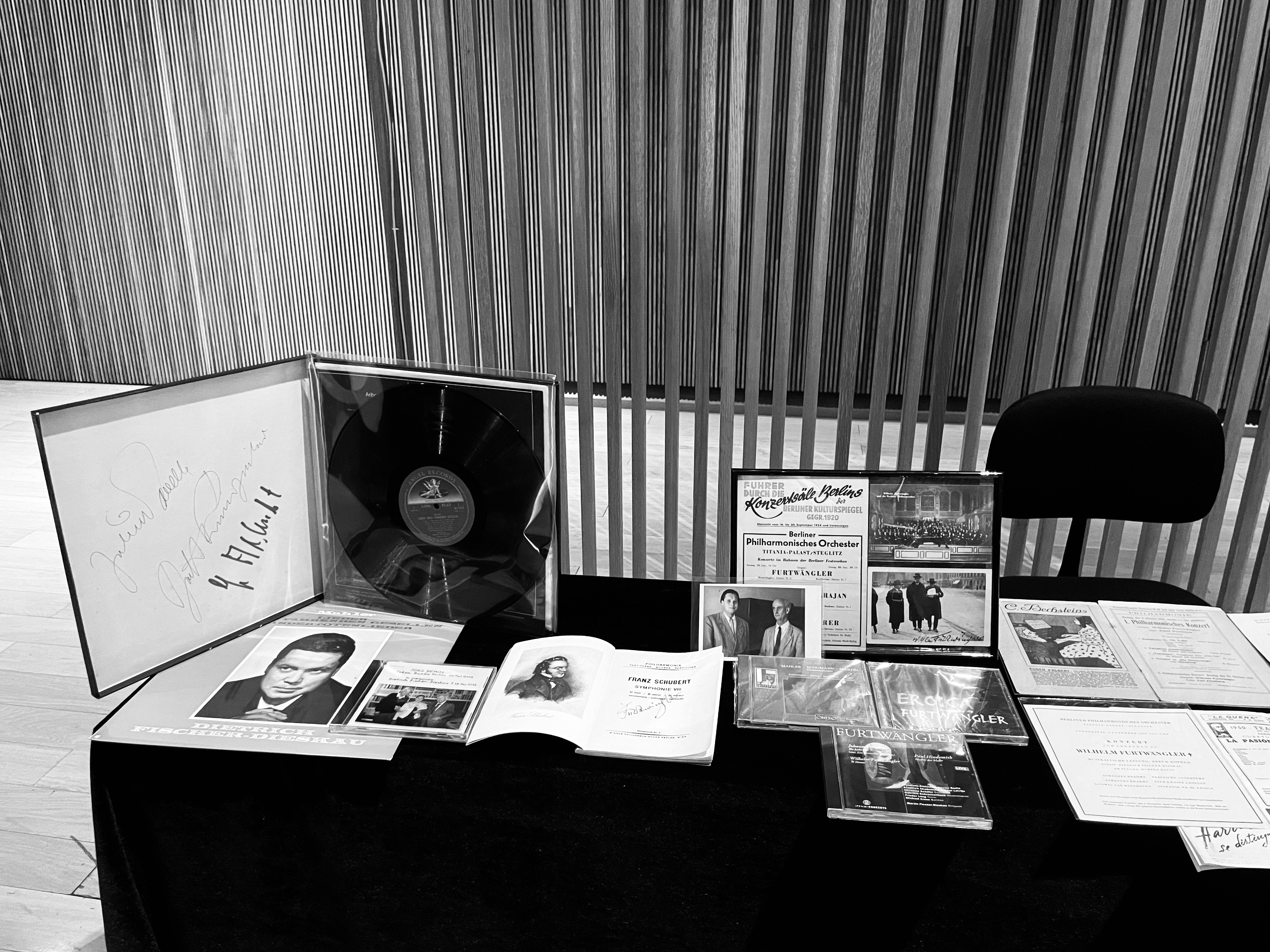

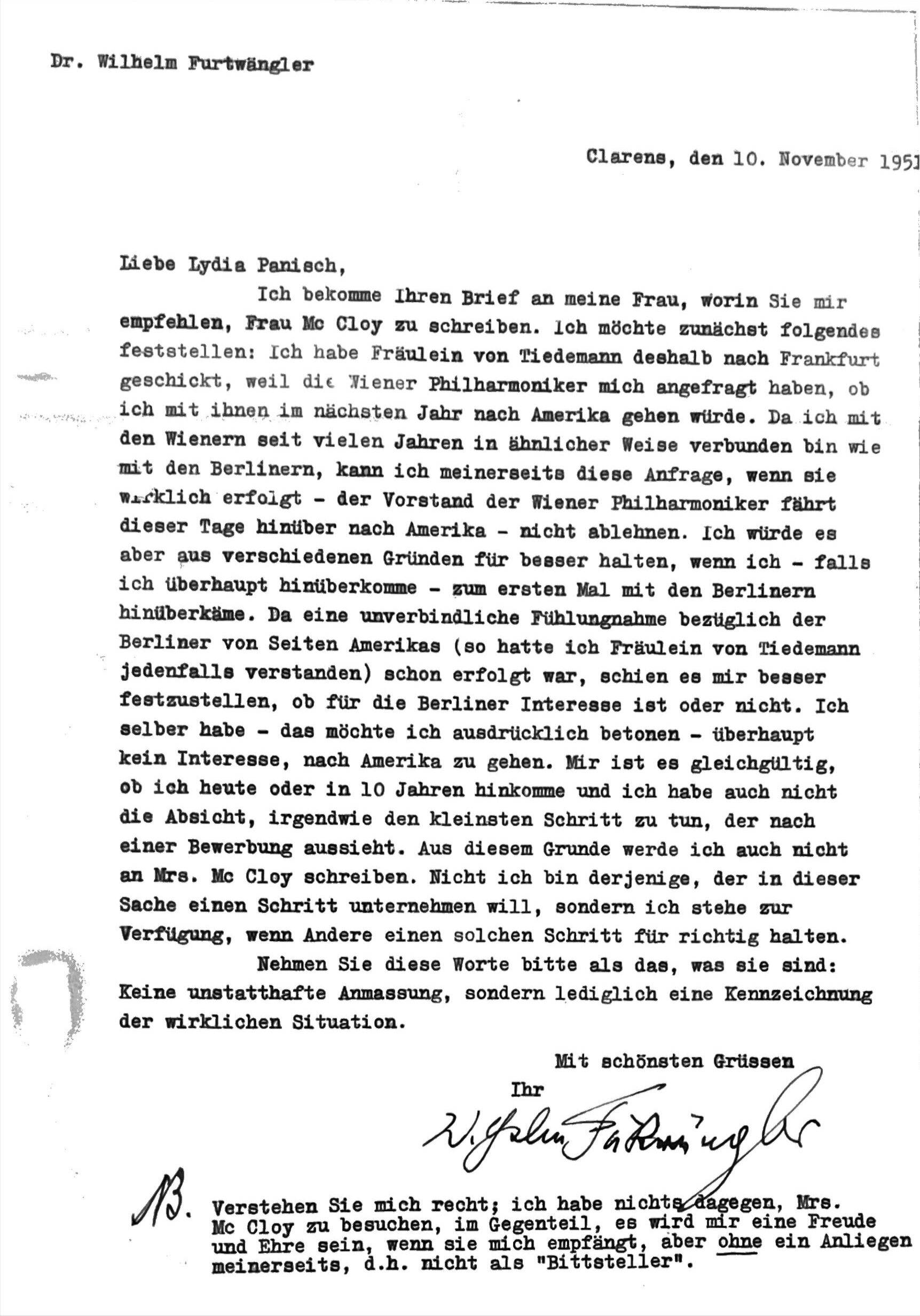

There is no need to repeatedly emphasize the importance of Wilhelm Furtwängler, and 30 November 2024 was the 70th anniversary of his passing. Maestro Martin Fischer-Dieskau also has a deep affinity with Furtwängler. His father, unquestionably one of the greatest and most influential singers of all time, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, who had been introduced to Furtwängler by his wife, gained Furtwängler’s appreciation at a very young age and shined on the world stage through the old maestro’s guidance. They became very close friends and left many unforgettably tremendous performances and recordings. Exactly 30 years ago, on Nov. 29, 1994, Maestro Martin Fischer-Dieskau also conducted the Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin in the concert commemorating the 40th anniversary of Furtwängler’s death with a program of Brahms, Hindemith and Furtwängler’s Te Deum. A live recording is issued on CD (IPPNW-CD-40).

The concert was always flowing in the “Furtwängler way”, as evidenced by Maestro Fischer-Dieskau’s involuntary sighing and humming while conducting, as well as by the marginalization of the beat. This is, of course, only on the superficial side, and the Furtwängler touches really are from the music itself. The conductor’s technique and cues are clearly in the Kapellmeister tradition, and he certainly has given the Harbin Symphony Orchestra a German-Austrian sound. If one could use a Lacanian description, Maestro Fischer-Dieskau’s conducting enjoys a style with an absence of the Big Other not only in terms of his movements but also in terms of effectively bringing out this special interpretation, focusing on the flow while generating the musicians enough room to play.

The concert opened with the overture to Wagner’s Der fliegende Holländer. This was a Furtwängler speciality, and it was Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau’s dream to perform the entire opera, but he only has left us a studio recording (if not the best ever) in which he sang the title role of The Dutchman. In the Romantic period, music developed fully into an immense spiritual force, with an impact far beyond the music itself, and Wagner represented this development, which Furtwängler then inherited. For Furtwängler, music was a “tool for understanding the world”.

The orchestra’s richness of sound in the opening scene and the fact that the strings in many fast passages of the work do not start on the downbeat made it more technically difficult for the orchestra to play, and it is interesting to note from past audiovisual recordings that Furtwängler’s orchestra, when faced with such moments, the bows would often not stay entirely on the strings, thus enabling a better uniformity, an approach which Maestro Fischer-Dieskau borrowed in his performance. This proved to be successful and correct, of course, thanks to the conductor’s dedication to the Harbin Symphony Orchestra in rehearsal, striving for precision in every bow, giving the orchestra a full sense of storm. In the face of Wagner’s grandeur, Maestro Fischer-Dieskau did not deliberately emphasize any single section but rather harmonized the music itself with a straightforward logic. The “Furtwänglerian Legato”, mentioned many times in his lecture, and the understanding and expression of musical continuity are clearly reflected in this performance. The accelerando passages are often drawn out, giving musicians room to manoeuvre. Another important moment appears right after the calmer phrase near the end, where the last three bars are suddenly marked as Presto. This is also a tribute to the Furtwängler way.

The subsequent Wesendonck-Lieder was performed four times by Furtwängler between 1920 and 1952 with the Nationaltheater-Orchester Mannheim, the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, the Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich, and the Philharmonia Orchestra. Unfortunately, no recording of them existed.

These songs were written when Wagner had a love affair during his exile in Zürich. At that time, Wagner was studying Schopenhauer, and he was caught in the contradictory entanglements of pursuing pure love and not being allowed to see his lover. Although the Wesendonck-Lieder is not as grandiose as his operas, it is a glimpse of Wagner’s philosophical thinking and a wonderful epitome of the forthcoming Tristan und Isolde.

Mezzo-soprano Chunqing Zhang’s voice is thick and three-dimensional with a stable vocal line, and the timbre of the higher notes sounds heroic with a physical penetration. Maestro Fischer-Dieskau leads the orchestra with exact gestures while constantly guiding the singer through coordination with the orchestra, which under his command was rich in brilliant colours, with a stretching of the important breath, fully capable of revealing intense fragments of the phrases. The viola solo especially stands out with its lyricism and warmth. The solo voice stands out as the main subject, but it is also shaped by the conductor as a guide to Mottl and Wagner’s excellent orchestration. After the third song Im Treibhaus, the singer’s performance improves, and the last two songs with melancholic colouration are even more moving, showing Wagner’s long lines and accumulation of emotions, as well as releasing them at the right place. The echo between the woodwinds and the voice in the fourth song, Schmerzen, is particularly moving. In Träume, the orchestra expands its full energy and dynamics together with the singer.

The second half of the concert has The Great Symphony in C major by Schubert. This is indeed the highlight of this program, and Furtwängler’s wartime recording from his “heroic creative period” with his Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra of this work is considered an absolute legend, which Maestro Fischer-Dieskau elucidates that it contains a “greatness” from nature and divinity.

The fact that Maestro Fischer-Dieskau is a superb conductor goes beyond his appearance at this concert. The full score and all the parts are from his personal collection, and based on his meticulous study of Furtwängler’s interpretation, he has hand-marked every single change in tempo, dynamic, expression, and even every important fingering, bowing, string glissando while changing positions, breathing places for winds and so on for every musician. Such detailed preparation ensured that this special concert was performed in the Furtwängler way as best as possible.

In addition, the conductor also obtained all of the small but extremely distinctive alterations that Furtwängler made to the score. For example, in the development section of the first movement, from bar 199 to 223, the ending notes of the trombone’s short phrases are extended to the beginning of the next phrase, filling in the sudden blanks, therefore connecting the flow of the phrases, which is also an exploration of the lyricism and extension of Schubert’s musicality by the trombone’s opulent timbre. It is also a manifestation of what the conductor said in his lecture about Furtwängler’s “breath”: it does not deprive the phrases as a whole and significantly enhances the continuity. There are also a number of timpani rolls in this movement, which are added by Furtwängler to generate more energy.

The overall tempo is on the fast side and exposition repeats were deleted in the outer movements, which, of course, had been Furtwängler’s treatment and a Romantic tradition. Maestro Fischer-Dieskau handled Schubert’s long, meandering melody with deft ease, at the same time uncovering the upward spirit of the excavation, which was particularly evident in the first movement, where he accelerates noticeably several times in the second half without letting it seem like a subjective treatment, with the trombones playing with extra bravura, and throughout the conductor’s acoustic shaping, these elements naturally grew energetically out of the music itself. Furtwängler replaced some violin pizzicato with arco in this movement, this nowadays rarely heard treatment also stands out in the concert.

Furtwängler’s emphasis on Schubert’s concept of Der Wanderer in the second movement, from the thematic material to the overall expression, is carried forward by Maestro Fischer-Dieskau, and the woodwinds are in good shape. The sudden and long pause, just like what Furtwängler did, before the last appearance of the theme in the B section of the ABABA structure caused the whole audience to fall silent, and for that moment we held our breath and had no clue when the music will start again. Such a stirring effect is another example of the conductor’s masterful control and deep understanding of Furtwängler’s signature treatment of inter-temporal reproduction. Under the baton, the woodwinds’ importance is strengthened, and the flow is reserved while accurately giving cues to the corresponding instruments without micromanaging the musical autonomy.

The Scherzo has a strong weaving sense. There exists the powerful solemnity and rhythmic tension brought out by the wind section, which gives the orchestra energy and gradually transforms it into a heroic temperament as the music progresses. Moreover, the elegance and nobleness brought out by the strings give the orchestra a singing quality, originating from the music’s dance element. Under Maestro Fischer-Dieskau’s baton, the orchestra releases a lavish acoustic, not only horizontally within the changes of form but also vertically in the pyramid of multiple emotional layers.

In the finale, the conductor opts for a deeper exploration of the Beethovenian elements and heroic core of Schubert’s music, with many frantic accelerations and intensifications that are so idiosyncratically Furtwänglerian, achieving more pronounced contrasts between light and dark and an even better representation of the romantic complexion. The timbre of the woodwinds reminds the audience of Beethoven’s works, and this character circumspectly spreads to the whole orchestra. When confronted with the melodic fragments of the theme, Maestro Fischer-Dieskau demands an imperceptible and faint ritardando in the Furtwängler style, without being interrupted by any subjective accentuation so that the audience can better capture the perceptual changes. This sensual decision comes from both Furtwängler and Fischer-Dieskau’s rational and profound investigation of the score. In order to strengthen the crescendo when the second theme appears again from bar 309 to 332, the score for the trumpet part is altered by adding upward chromatic elements, which was another of Furtwängler’s genius Retuschen. At the end of the symphony, there was no exaggerated closing gesture. The arms fell naturally in the position where the music stopped, and the whole concert ended in the aforementioned prominence of the absence of the Big Other.

The entire concert was performed in the Furtwängler way, and after many comprehensive rehearsal hours, the playing of the Harbin Symphony Orchestra was remarkable. Having conducted the concert entirely from memory, which again comes from Furtwängler’s strong intention that all conductors should entirely memorize their scores. Prof. Dr Martin Fischer-Dieskau is undoubtedly a master in music, but not only in music. In his lecture, he referred to the “Furtwänglerian idea”, namely the rejection of historicism and the integration of conductor and orchestra to manifest the composer’s intentions. In this concert, at least, the conductor succeeded in transmitting, interpreting and presenting this Furtwänglerian idea to the Harbin audience.

The 20th century has seen a tidal wave of great conductors, but no one has been able to reach what Furtwängler achieved, and many of the 21st century’s successors have drifted far away from what Furtwängler’s era defined as conducting. Many try to produce a divergent sound while doing the classic repertoire just for the sake of being individualized, yet all the innovations should not be separated from the musical origins. Looking back to Furtwängler’s performances, reviewing his artistic sophistication can unquestionably lead to the contemplation of the real need for musicians today. “Playing in the way Furtwängler did” includes a learning process from his way of interpreting but not reproducing, because the same way can always lead to different results, just like every Furtwängler concert, when even two consecutive performances of the same work could contain drastic but cerebral differences. Furtwängler’s approach to music is much freer, highlighting a kind of mutual improvisation in many cases, and there are always people who criticize Furtwängler for being a subjectivist. However, if one understands better, one will recognize that the constant tempo changes are not from any self-indulgent imagination but from deep analysis and apprehension of the music from a composer’s point of view, all striving to attain the only correct answer in Furtwängler’s heart.

By honouring Furtwängler today, 70 years after his passing, we are also perpetuating and continuing the search for the true meaning of the music he, and many grandmasters, pursued.